Foreword

In the first part of Chantal Akerman by Chantal Akerman, the “auto-portrait” she made for French cultural TV channel Arte, the Belgian filmmaker talked about an idea she once had: inspired by the sight of her next-door neighbour’s daily morning exercises, she would make a film about a woman who does tai chi every day, rain or shine. And it “would have to be funny, side-splitting”, she said in earnest.

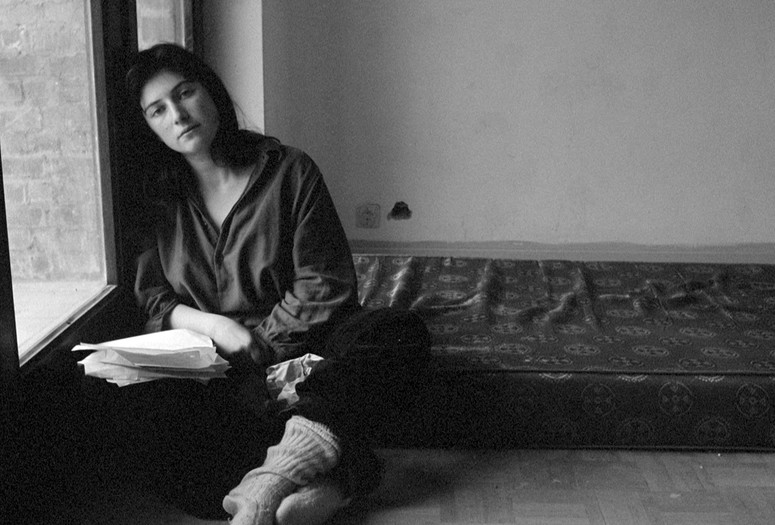

That film never came to pass – and, sadly, never will, as we mourn her passing on October 5, 2015 at the age of 65. Still, that sketch reveals a lot about the director: her inventive mischief, maybe, but also her intent in teasing drama and meaning out of the mundane through the interplay of time and space. This is, after all, someone whose pièce de resistance is a three-hour-plus film about a housewife’s daily routines within the confines of a non-descript apartment.

But there’s more to Akerman than her austere, formalist experiments. She’s much more complex an artist and a person than some of her best-known works might suggest: she’s also warm, generous and funny in her own way, something reflected by both her loyal following and also the closely-knit community of collaborators she worked with nearly throughout her five-decade-long career.

The title of this mini-retrospective, Looking To (Not) Belong, was rooted in Akerman’s recollections, in an interview with French critic Nicole Brenez, of how she felt of “looking to belong, even for just a second”, with the orthodox Jews she saw on the streets. This desire to be part of something, however, runs against her well-documented pride – a defiance fueled as much by determination and circumstances – for “not belonging anywhere”.

She has long been adamant she’s not making “women’s films”, and that her films are not be shown at LGBT festivals – despite her standing as a pioneer in feminist, queer cinema. (In her own production notes for Jeanne Dielman, this line precedes the list of names for the all-female crew: “By choice, the team was composed essentially by women.”)

Such contradictions illustrate Akerman’s long-running battle with her multiple identities: the “Jewish girl” born to a family of Holocaust survivors, a woman and gay filmmaker carving her career in a world of heterosexual men, a taboo-breaking artist transcending the barriers of cinema and visual arts. Her films are formalist breakthroughs and are clarion calls for social justice, while also dabble with deconstruction of existent generic tropes and refuse to subscribe to grand narratives.

As a result of Akerman’s reluctance to conform to norms and fads and easy sloganeering, her films have remained timeless in their shape and raw in its spirit. Just as much as she admitted to be the torch-bearer of filmmakers from generations past – Charlie Chaplin, Jean-Luc Godard, Michael Snow, Yvonne Rainer, among others – she has produced a body of work which has left a mark on films by disparate filmmakers such as Gus Van Sant, Sofia Coppola, Michael Haneke, Kelly Reichardt, Céline Sciamma and Apichatpong Weerasethakul.

Back to Chantal Akerman par Chantal Akerman: in her monologue, Akerman admitted how her films revolve around several themes: language, documentary, fiction, Jews and the Second Commandment are “all in her films”. Taking a cue from that, we’ve decided to eschew chronology for this retrospective, and instead take the liberty of shaping the programme under five key words which we believe define Akerman’s work.

“Inside(s)” is concerned with the revelation of confined bodies and emotions. “Exiles” explores films reflecting characters – real and imagined – fleeing from the burden of history and social norms. The third part tackles Akerman’s audacious dissection of how “desires” could manifest themselves, as yearning and also as suppression. “Witnesses” provide proof of how the filmmaker looks beyond her own autobiography to empathise with the pains of others. “Rhythms” is designed to highlight the filmmaker’s masterful ability to make routines matter. Finally, “Mothers” is dedicated to the figure looming large over Akerman’s films and her life.

For all her achievements, Akerman’s work remains undervalued in Hong Kong in comparison to her contemporaries. Hopefully, Looking To (Not) Belong could contribute to rectify this, and we have to thank the Consulate General of Belgium in Hong Kong and Macau for their support. Meanwhile, we would also like to thank Akerman’s long-time collaborators for their generous assistance in bringing this programme to fruition – and in making Chantal’s films sing again.

Clarence Tsui

Director, Broadway Cinematheque

The title of this mini-retrospective, Looking To (Not) Belong, was rooted in Akerman’s recollections, in an interview with French critic Nicole Brenez, of how she felt of “looking to belong, even for just a second”, with the orthodox Jews she saw on the streets. This desire to be part of something, however, runs against her well-documented pride – a defiance fueled as much by determination and circumstances – for “not belonging anywhere”.

She has long been adamant she’s not making “women’s films”, and that her films are not be shown at LGBT festivals – despite her standing as a pioneer in feminist, queer cinema. (In her own production notes for Jeanne Dielman, this line precedes the list of names for the all-female crew: “By choice, the team was composed essentially by women.”)

Such contradictions illustrate Akerman’s long-running battle with her multiple identities: the “Jewish girl” born to a family of Holocaust survivors, a woman and gay filmmaker carving her career in a world of heterosexual men, a taboo-breaking artist transcending the barriers of cinema and visual arts. Her films are formalist breakthroughs and are clarion calls for social justice, while also dabble with deconstruction of existent generic tropes and refuse to subscribe to grand narratives.

As a result of Akerman’s reluctance to conform to norms and fads and easy sloganeering, her films have remained timeless in their shape and raw in its spirit. Just as much as she admitted to be the torch-bearer of filmmakers from generations past – Charlie Chaplin, Jean-Luc Godard, Michael Snow, Yvonne Rainer, among others – she has produced a body of work which has left a mark on films by disparate filmmakers such as Gus Van Sant, Sofia Coppola, Michael Haneke, Kelly Reichardt, Céline Sciamma and Apichatpong Weerasethakul.

The title of this mini-retrospective, Looking To (Not) Belong, was rooted in Akerman’s recollections, in an interview with French critic Nicole Brenez, of how she felt of “looking to belong, even for just a second”, with the orthodox Jews she saw on the streets. This desire to be part of something, however, runs against her well-documented pride – a defiance fueled as much by determination and circumstances – for “not belonging anywhere”.

She has long been adamant she’s not making “women’s films”, and that her films are not be shown at LGBT festivals – despite her standing as a pioneer in feminist, queer cinema. (In her own production notes for Jeanne Dielman, this line precedes the list of names for the all-female crew: “By choice, the team was composed essentially by women.”)

Such contradictions illustrate Akerman’s long-running battle with her multiple identities: the “Jewish girl” born to a family of Holocaust survivors, a woman and gay filmmaker carving her career in a world of heterosexual men, a taboo-breaking artist transcending the barriers of cinema and visual arts. Her films are formalist breakthroughs and are clarion calls for social justice, while also dabble with deconstruction of existent generic tropes and refuse to subscribe to grand narratives.

As a result of Akerman’s reluctance to conform to norms and fads and easy sloganeering, her films have remained timeless in their shape and raw in its spirit. Just as much as she admitted to be the torch-bearer of filmmakers from generations past – Charlie Chaplin, Jean-Luc Godard, Michael Snow, Yvonne Rainer, among others – she has produced a body of work which has left a mark on films by disparate filmmakers such as Gus Van Sant, Sofia Coppola, Michael Haneke, Kelly Reichardt, Céline Sciamma and Apichatpong Weerasethakul.

Back to Chantal Akerman par Chantal Akerman: in her monologue, Akerman admitted how her films revolve around several themes: language, documentary, fiction, Jews and the Second Commandment are “all in her films”. Taking a cue from that, we’ve decided to eschew chronology for this retrospective, and instead take the liberty of shaping the programme under five key words which we believe define Akerman’s work.

“Inside(s)” is concerned with the revelation of confined bodies and emotions. “Exiles” explores films reflecting characters – real and imagined – fleeing from the burden of history and social norms. The third part tackles Akerman’s audacious dissection of how “desires” could manifest themselves, as yearning and also as suppression. “Witnesses” provide proof of how the filmmaker looks beyond her own autobiography to empathise with the pains of others. “Rhythms” is designed to highlight the filmmaker’s masterful ability to make routines matter. Finally, “Mothers” is dedicated to the figure looming large over Akerman’s films and her life.

For all her achievements, Akerman’s work remains undervalued in Hong Kong in comparison to her contemporaries. Hopefully, Looking To (Not) Belong could contribute to rectify this, and we have to thank the Consulate General of Belgium in Hong Kong and Macau for their support. Meanwhile, we would also like to thank Akerman’s long-time collaborators for their generous assistance in bringing this programme to fruition – and in making Chantal’s films sing again.

Clarence Tsui

Director, Broadway Cinematheque

Back to Chantal Akerman par Chantal Akerman: in her monologue, Akerman admitted how her films revolve around several themes: language, documentary, fiction, Jews and the Second Commandment are “all in her films”. Taking a cue from that, we’ve decided to eschew chronology for this retrospective, and instead take the liberty of shaping the programme under five key words which we believe define Akerman’s work.

“Inside(s)” is concerned with the revelation of confined bodies and emotions. “Exiles” explores films reflecting characters – real and imagined – fleeing from the burden of history and social norms. The third part tackles Akerman’s audacious dissection of how “desires” could manifest themselves, as yearning and also as suppression. “Witnesses” provide proof of how the filmmaker looks beyond her own autobiography to empathise with the pains of others. “Rhythms” is designed to highlight the filmmaker’s masterful ability to make routines matter. Finally, “Mothers” is dedicated to the figure looming large over Akerman’s films and her life.

For all her achievements, Akerman’s work remains undervalued in Hong Kong in comparison to her contemporaries. Hopefully, Looking To (Not) Belong could contribute to rectify this, and we have to thank the Consulate General of Belgium in Hong Kong and Macau for their support. Meanwhile, we would also like to thank Akerman’s long-time collaborators for their generous assistance in bringing this programme to fruition – and in making Chantal’s films sing again.

Clarence Tsui

Director, Broadway Cinematheque